In 1978, there were 542 black men in medical school in 2014, that number was 515. He read plays by August Wilson that took place in the same Pittsburgh neighborhoods where Freedom House medics lived and worked, and walked around imagining what it was like to be an EMS worker at the time.įor Edwards, who identifies as African-American, examining and retelling the history had a powerful impact on his experience as a physician. In addition to studying the archival material, Edwards steeped himself in the period he was writing about. Matthew Edwards conducted most of his research in the Harvard University archives of Freedom House medical director Nancy Caroline. "I had so many different questions and I couldn't find much online." "I thought, 'This is a really cool program, why haven't I heard about it?'" Edwards said. After his second year of medical school, he won a grant to spend part of his summer researching the archives of Freedom House medical director Nancy Caroline at Harvard University's Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. He first read about Freedom House while he was a medical student researching another topic. "That's a part of the story that really resonated with me."Įdwards is in his third year of residency in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, with interests in medical history and bioethics. "There are so many people who can contribute to medicine and health care and society, who often are not given an opportunity," Edwards said. And while many cities contributed to the development of EMS, Freedom House became the gold standard for paramedic training, Edwards notes. In that way, the program met a dual need for jobs and better medical care in their communities. Safar's trainees, who would provide 24-hour emergency medical care and hospital transport in two districts, had previously held low paying or menial jobs and many lacked a high school diploma. His department would help them get ambulances to transport critically ill or injured patients with life support, if they would let him train EMTs and medics to staff them. Safar saw an opportunity to test out his vision for national standards in community-wide emergency care. In 1967, Safar was approached by leaders in the predominantly black community around Presbyterian University Hospital who wanted to provide better transportation for their residents to receive medical care. While at the University of Pittsburgh, Safar became focused on improving lifesaving measures in the critical moments before patients could get to a hospital. The experimental ambulance service began with the help of Peter Safar, MD, a critical care pioneer considered the father of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The Freedom House Ambulance Service, courtesy University of Pittsburgh

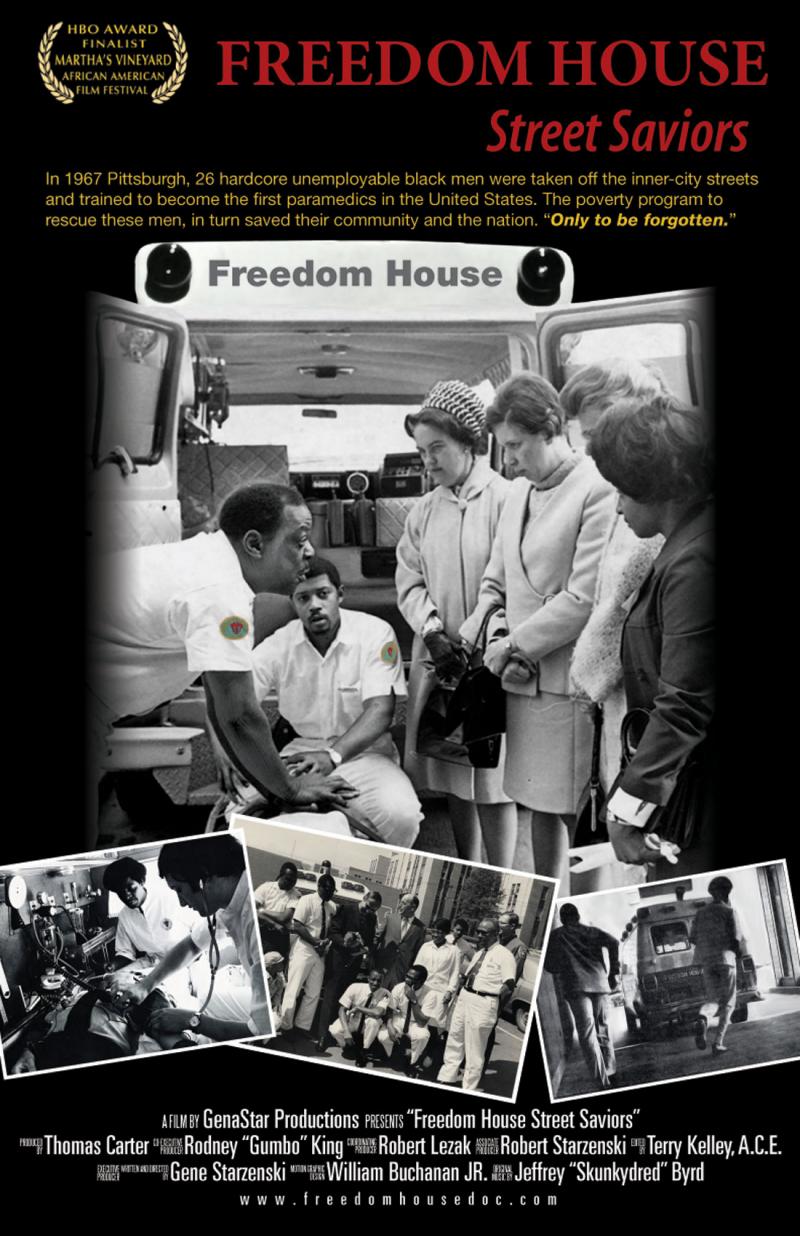

This is how Edwards opens his paper tracing the rise and fall of Pittsburgh's Freedom House ambulance project, an all-black paramedic service that ran from 1967-1975 and helped establish the national training model for emergency medical service programs. There was no attendant by the patient's side, and no life support equipment.īut just as astounding to the doctors, Edwards writes, was the medic standing before them: a poor black man from one of Pittsburgh's inner-city neighborhoods, previously considered "unemployable," now trained to provide advanced cardiac life support. Critically ill patients often got to the hospital in a station wagon or hearse driven by a police officer with minimal first-aid training. But at the time, in Pittsburgh, it was shocking for two reasons, writes Stanford resident physician Matthew Edwards, MD, in an article in The Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences.įor starters, the idea that a sick person would be brought to the ER by someone trained in medical care was still a novel concept. This scene unfolds countless times a day in hospitals around the country today. He gives a concise description of the patient's medical history, vital signs and physical exam to the doctors and nurses. An emergency medical technician stands in a hospital emergency room, presenting the patient he has brought in by ambulance.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)